Many of us have been watching the UEFA European Women’s Football Championship, also known as Euro 2022, to cheer on our national team these past weeks. In this 13th edition of the tournament, we’re seeing huge developments in the sport. Unlike tennis, the most gender-equitable sport for women, football still has a long way to go in terms of equality. As the biggest sport in the world, football is a prime example of how hard it is to break the chains of patriarchal traditions in our society.

Women’s football has been considered a lesser sport by some in the past due to its quality compared to men’s. But what we’re seeing now proves that quality is not the issue, but rather funding and exposure. Women have not had the same opportunities to go professional as men due to a lack of funding and sponsors in their leagues. The prize money in tournaments is generally still much lower than for the men’s teams and live coverage of matches has been limited. Sports brands have only recently started producing football boots made specifically with women’s physique in mind and some of the world’s biggest football clubs have only just added a women’s team. Women’s football was also banned in England from 1921 to 1970, as it was in many other countries, and girls have long been discouraged from playing football in school. This kind of discrimination has kept the sport from developing for decades and has caused damage that will take as long to repair.

Fortunately, things are changing. The US women’s team now has an equal salary to the men and the gender pay gap in prize money for tournaments is slowly closing. More sponsors are getting involved, media coverage is increasing and audiences are growing fast. We’ve seen record after record being broken in recent years and with 69,000 fans attending the opening game of Euro 2022 at Old Trafford stadium in Manchester things are certainly looking up.

Audiences at home are also increasing, with 7.6 million viewers having watched England beat Spain in the quarter-final on BBC One and that record will most likely be broken on Sunday with as many as 90,000 attending the final where England faces Germany. This will make Euro 2022 the biggest ever women’s sporting event in Europe and it’s already created unforgettable moments, like Alessia Russo’s outrageous back-heeled goal in England’s surprising thrashing of Sweden in the semi-final. The tournament has provided excellent games, brilliant performances from players that will surely make the history books and, perhaps more than ever before, the English fans once again have hope that on Sunday it’s coming home.

A badge of identity

Another important development has caught people’s attention at this tournament – we’re seeing a lot more women’s teams with their own unique kits – yes, this blog has a creative angle too!

Some may argue that wearing different kits to men’s teams only increases inequality, but I think the opposite is true. The empowerment of having your own identity is invaluable and shows recognition that there’s no need to be compared to the men’s team because they’re independent of them. They’re still playing for the same nation, but they’ve got the opportunity to make their own history and celebrate their own heroes with equal support from their countries.

I personally loved seeing some of the exciting designs featured on this year’s women’s kits. Sports brands tend to give similar designs to all their teams which reduces the individual creativity of each kit. It often feels like a missed opportunity not to show what makes each nation unique, so it’s a welcome change to see some of the teams wearing bespoke designs with interesting patterns and nods to each nation’s history.

England’s kit features a subtle diamond print with shiny, pearl-like badges that gives tribute to all the shining lights that have advanced women’s football. The typeface used on their backs is a form of an Old English typeface (also known as blackletter or gothic type) which complements the sharp edges of the diamond pattern.

The Netherlands pay homage to the De Stijl art movement on their away kit with blocks of primary colours that also hint at their nation’s flag. Sweden has included a guide on ‘How to stop Sweden’ printed on their kits to show their confidence with lines like “first of all, Sweden is one of the fastest-playing teams in the world and also one of the very best at counter-attacking, do everything you can to reclaim the ball once you lose it… try to force the Swedish players down the sidelines and close them down aggressively.”

The French kit features ornate floral patterns inspired by neoclassical Gallic art and Liberty of London collaborated with Puma on adding rose patterns to the kits of Italy, Switzerland, Iceland and Austria. Of course, none of these kits is wildly changed from the men’s design as they still belong to the bigger brand of that national team. If the Netherlands stopped playing in neon orange their fans couldn’t call themselves the Orange Legion and the French supporters couldn’t be The Blues. However subtle, these embellishments show confidence in the teams and in women’s football. They have an equal claim to the brand colours and the right to make it their own so that they can grow a stronger identity for themselves.

Branding and belonging

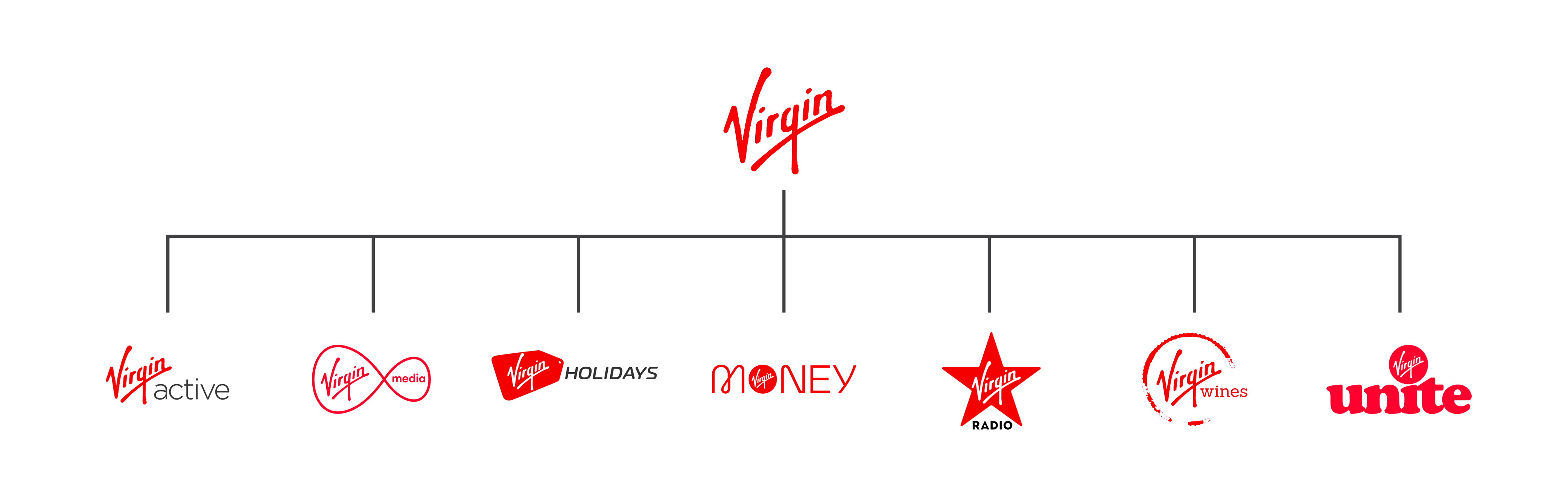

The same principle works for businesses that have different arms that need sub-brands. Virgin Group has several sub-brands like Virgin Active, Virgin Media, etc, and they’re all recognisably parts of the overarching brand. The audience knows what the brand stands for so it’s easier to apply those expectations and values to the sub-brands and it also allows for new elements to be introduced.

Sometimes newcomers can enhance the image of the greater brand, think of what Air Jordans did for Nike when Converse was the biggest sportswear brand for basketball or what PlayStation and Xbox did for Sony and Microsoft when Sega and Nintendo practically owned the video game console market.

The Lionesses are a pack of their own, with amazing players that have impressed and inspired us all. But they wear the same colours and the Football Association’s badge as the men’s team. You could even argue for the women’s team to have their own badge, with three lionesses instead of lions. But the three lions are taken from the royal arms of England and replacing them with lionesses might send the message that the FA’s main badge is reserved for the men’s team so then a new overarching identity would be needed to ensure equality.

Evolving brand identity

Evolving brand identity

The audience for women’s football is generally the same as men’s football – it’s people who like football. But there are some social distinctions. The macho energy and hooliganism that can be associated with men’s football can be off-putting to some and certain aspects of its culture can alienate people that don’t feel comfortable or accepted in that environment.

Homophobia, racism and sexism are constant issues in the sport and reports of domestic violence skyrocket during every major tournament. Thankfully, women’s football has a better track record of tolerance and one hopes that those values are upheld and even transferred as it becomes more widely celebrated.

When Coca-Cola released Coke Zero in 2005 it was aimed at young males based on market research that men didn’t like to be associated with “diet” drinks, so they were less likely to buy Diet Coke. Coke Zero became hugely popular, partly because it tasted more like the full-fat version of the drink than Diet Coke and used the words “zero calories” instead of “diet”.

This sub-brand was replaced with Coca-Cola Zero Sugar in 2017 with an updated formula – a look that is closer to the original and marketing aimed at all genders. It seems that after realising that a certain group of males was excluded from their diet drinks, Coca-Cola created a brand that filled that gap. Then, once the sub-brand had grown strong enough, it changed again to distance itself from gender separation and united the market into one: people that like Coke without the calories.

Women’s football and men’s football should both stand equal as sub-brands of football. So why do we have the Premier League and the Women’s Super League? If one brand needs to be gender specific surely both should be. Women’s football is no different to men’s football. It’s just football. We might not see it change into a mixed-gender sport but we’re certainly seeing that women’s football deserves just as much attention and support as the men’s.

When allowed to grow, women’s football can not only provide entertainment, inspiration and careers to those excluded from the men’s game but also influence men’s football to become more tolerant and inclusive. Everyone benefits as it will make the biggest sport in the world even bigger and serve as a model for others to follow in terms of equality. By elevating the brand of women’s football and building on its values of inclusivity in its love of the game we’re bound to see advancements in the sport in its entirety. It’s only right that the beautiful game should lead by example by celebrating beauty in all its forms and giving everyone an equal chance to play and enjoy it.